The impact of US elections on equities

What will Joe Biden's election mean for investors?

The conclusion of the US elections in the last few weeks dragged on for days, and the official results for weeks, as the electoral workers counted all the postal votes.

But the results that the polls were predicting - a Joe Biden win - were borne out, even if it was not the landslide they were pointing to.

But what does this mean for investors in US equities?

On the one side, US companies and people may no longer be able to rely on tax cuts from Donald Trump, but on the other there is a more predictable, experienced politician, who is taking active steps to address the pandemic.

And there are more structural issues to contend with. The US is home for most of the biggest tech stocks in the world, all of which have done well during the pandemic, as we rely more heavily on technology.

Is this a good thing for investors? What about the stocks that fall into a value category? Will there be a long-term structural shift in investing style, and where should an investor look if he or she is trying to get into the US market?

This special report aims to address some of these questions, and the CPD feature is worth an indicative 30 minutes' CPD

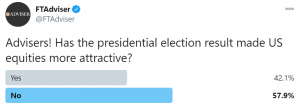

Advisers split on US election

Advisers are split on the consequences of the US election outcome for client portfolios, according to the latest FTAdviser poll.

The election of Joe Biden as US president has made US equities more attractive for 42 per cent of those advisers surveyed, while the outcome is either negative or makes no difference to the attractiveness of the US market at this time.

Mr Biden has pledged to introduce a wave of extra government spending as a way to potentially boost growth, but Mr Biden’s ability to do this at the scale mentioned in his campaign is constrained by his party not having won control of the Senate.

Mr Biden had spoken, during his campaign, of aiming for a stimulus package of $2trn, but a figure of between $500bn and $1trn is now more likely.

The pandemic has also resulted in the US Federal Reserve, that country’s central bank, cutting interest rates to record low levels.

A combination of some fiscal stimulus and the monetary policy response would typically be expected to create inflation in an economy, which would normally be expected to be positive for equities and bad for bonds.

If inflation and growth rise at a particularly fast rate, this would likely lead to growth stocks outperforming relative to value stocks.

Stefani Reynolds/Bloomberg

Stefani Reynolds/Bloomberg

David Paul Morris/Bloomberg

David Paul Morris/Bloomberg

Victor J. Blue/Bloomberg

Victor J. Blue/Bloomberg

A Biden bounce?

Many of the conundrums that have captured investors' thoughts in recent years have been brought to the boil by the pandemic; in the years to come it is likely to be in the performance of the US equity market where investors get some answers to those long-standing questions.

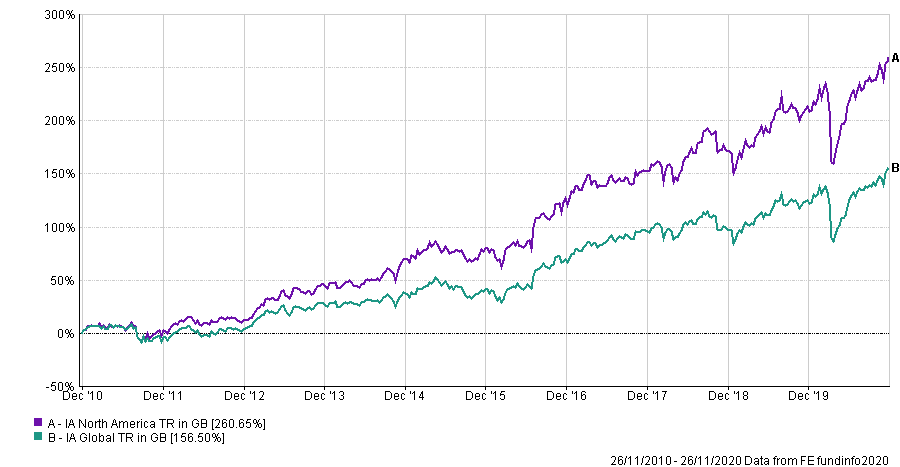

Investors in US shares have seen a return of 98 per cent over the five years to November 24 2020, sharply outperforming the 80 per cent returned by the IA Global sector in the same time period.

The outperformance derived largely from the returns generated by a handful of large technology companies, and placed that market at the centre of the debate between those market participants who favour the growth style of investing, and those who focus on the value style.

Growth Giants

Growth stocks tend to perform best when there is little economic growth or inflation. In this climate, those relatively few companies which are growing, and which have strong potential for future growth, trade at higher than historical average valuations, while the rest are out of favour.

This theme disproportionately benefited the US equity market, as a major chunk of the economic growth that has occurred over the past decade has come from technology stocks, of which the US has many, at the expense of traditional banks, retailers, and industrial companies which are usually viewed as value stocks, and which predominate in the UK and European markets.

The conditions which typically cause a switch between styles are when economic growth and inflation rise. This is because, in such an environment, many companies will be growing, so investors are prepared to pay less of a premium for growth.

Instead, with broad based economic growth, investors prioritise the valuations at which companies trade.

The rise of technology stocks is the result of a profoundly changing world, where long-standing business models are in permanent decline

For the decade after the financial crisis, growth and inflation remained sluggish.

Advocates of the value style of investing said “the elastic would have to snap” as investors, surveying comparatively benign economic conditions alongside ever rising valuations for growth stocks, would eventually move to value.

For the most ardent growth investor, the rise of technology stocks is the result of a profoundly changing world, where long-standing business models are in permanent decline, and historical comparisons are otiose.

The pandemic seemed, at first, to answer the question as the way people live, worked, and consumed changed, instantly benefitting the large technology growth companies, while the more cyclical areas that would typically be held in value portfolios, such as airlines, banks and supermarkets suffered.

But the debate is far from settled, according to Neil Veitch, who runs the SVM World Equity fund.

He acknowledges that it has been a tough time for value investors: “Waiting for value to perform has been akin to waiting for Godot.

“The announcement of a vaccine, plus the election result, is very good for value.

“We are going to see a synchronised global recovery, with low interest rates and a fiscal stimulus, if you look through the very short-term, then those are the market conditions where a rally in value stocks is quite likely."

Political purse strings

A major difference between the economic conditions that prevailed after the global financial crisis, and the policy response to the pandemic-induced recession, is that this time the interest rate cuts and quantitative easing have been accompanied by increases in government spending, an additional stimulus that lead to higher growth.

But Fahad Kamal, chief investment officer at wealth management firm Kleinwort Hambros is more sceptical.

I never invest based on election results because I think those are things we cannot predict

He says the conditions which have prevailed in the world for the past decade and led to the outperformance of growth stocks, such as high debt levels, ageing populations, and technological change, will not only continue to be factors in the coming years, but have probably been exacerbated by the pandemic.

Mr Kamal adds: “I never invest based on election results, or based on what politicians promise because I think those are things we cannot predict.”

Chris Ralph, chief investment officer at St James Place, says the investors should also try to have both value and growth investments, as if there is a sharp shift in market sentiment and a client has all of their eggs in one basket, then the client would face losses.

He added that the US fund into which St James Place clients are invested: “hasn’t been the best performer over the past 18 months”, and is a value fund.

Richard Saldanha, global equity fund manager at Aviva, says the election outcome has actually been relatively positive for the large tech stocks. This is because while Joe Biden won the presidency, his party has so far failed to gain control of the senate.

This limits Mr Biden’s capacity to increase regulation on those companies, and so removes some of the uncertainty that may have been constraining the share price.

The second major question to be decided in the years ahead is whether the growing influence of emerging markets on the global economy will continue.

Since the global financial crisis it has been the case that China has become what economists call the “marginal buyer” in the world economy, that is, the power of the Chinese economy is such that it can drag the rest of the world out of recession, in much the same way that the US economy did for decades.

Despite this shifting of wealth eastwards, it is the US equity market that remains firmly in favour with investors.

Two of the reasons the US equity market is viewed in a generally favourable light in tough times, are that the dollar is a safe haven asset, and the market views political risk as being lower in the US.

But after a messy election process and with a ballooning budget deficit, do US equities continue to deserve a premium valuation relative to the rest of the world?

Mr Veitch says: “The US political system is filled with checks and balances, and so even when you get a politician like Trump, who is probably as bad as it can get in a democracy, he can’t actually do very much.”

James Beaumont, head of multi-asset portfolio management at Natixis Investment Solutions, believes it is likely that Mr Biden’s more internationalist approach, at least in comparison to that of Mr Trump, is likely to benefit equity outside of the US , at least relative to the president’s domestic market.

The US political system is filled with checks and balances, and so even when you get a politician like Trump, he can’t actually do very much

Mr Ralph says: “Investors have been saying for a decade that the US economy would run out of steam, but those are also the people saying that interest rates could not go any lower, and then they did.

“The US is still the best equity growth market in the western world, and in terms of market composition, tech companies will lead the way for the next decade.”

Simon Edelsten, who runs the £373m Mid Wynd International investment trust and other global equity mandates at Artemis believes the premium at which US equities tend to trade relative to the rest of the world is a function not of the world taking a political view, but rather as a result of the US market having tech companies.

He says it may be that US equities perform relatively less well in the coming years, because that economy and stock market did not fall by as much as the UK did, as that country never entered lockdown, so has less lost ground to recover.

Shaunak Mazumder, global equity fund manager at Legal and General Investment says: “A split Senate means that the risk of increased regulation on a few key sectors that are driving markets, including technology, communication services and healthcare is reduced, which bodes well for equity markets.

“The looming risk from the change in administration remains – the reversal of the corporate tax cuts put through by the Trump administration, which would have a negative impact on earnings growth and valuation of equity markets.

“This may however be balanced with much better management of Covid and a larger fiscal stimulus package, which would be positive for the real economy.”

Mr Saldanha says that one of the factors which has driven US equity outperformance in recent years has been the practice of some US companies of buying back their own shares.

Companies in that market tend to do this, rather than pay dividends, as this is more tax efficient in that jurisdiction.

Share buybacks directly boost the share price of a stock, and Mr Saldanha says that with many companies having taken a financial hit as a result of the pandemic, will have less free cash to use to buy back shares, removing one of the reasons why US equities performed well for the past decade.

Income angst

The final major question that will find resolution in the coming years is whether income investors need to permanently lower their expectations of the yield that can be generated from a portfolio.

Ron Temple, head of US equities at Lazard Asset Management, says the US market is unlikely ever to provide the solution to this dividend dilemma.

He says US investors tend to invest with capital gain in mind, and this means there is not quite the same pressure to pay dividends as companies in other markets may experience.

Arnab Das, global market strategist at Invesco says: “For the foreseeable future, the US model of capitalism points to a market driven by capital gains as a result of competitive pressures within sectors, between firms through innovation, efficiency and financial engineering reflecting the tax system.

“The US could well become an income-driven equity market in principle and in future, of course, but that would probably be the result of maturing beyond rapid structural change and technological progress, in combination with changes to the tax rules.

He says US investors tend to invest with capital gain in mind, and this means there isn’t quite the same pressure to pay dividends as companies in other markets may experience.

Arnab Das, global market strategist at Invesco says: “ For the foreseeable future, the US model of capitalism points to a market driven by capital gains as a result of competitive pressures within sectors, between firms through innovation, efficiency and financial engineering reflecting the tax system.

“The US could well become an income-driven equity market in principle and in future, of course, but that would probably be the result of maturing beyond rapid structural change and technological progress, in combination with changes to the tax rules.

“The combination of interest tax deductibility with heavy compensation for senior staff in equity and equity options, as well as competitive pressures to generate high shareholder returns through profits and buybacks.”

Mr Ralph says: “The US can’t be a big part of an equity portfolio, there is a much bigger appetite to buy back shares, and I don’t see that changing”.

He says US investors tend to invest with capital gain in mind, and this means there isn’t quite the same pressure to pay dividends as companies in other markets may experience.

Arnab Das, global market strategist at Invesco says: “ For the foreseeable future, the US model of capitalism points to a market driven by capital gains as a result of competitive pressures within sectors, between firms through innovation, efficiency and financial engineering reflecting the tax system.

“The US could well become an income-driven equity market in principle and in future, of course, but that would probably be the result of maturing beyond rapid structural change and technological progress, in combination with changes to the tax rules.

“The combination of interest tax deductibility with heavy compensation for senior staff in equity and equity options, as well as competitive pressures to generate high shareholder returns through profits and buybacks.”

Mr Ralph says: “The US can’t be a big part of an equity portfolio, there is a much bigger appetite to buy back shares, and I don’t see that changing”

AP Photo/Evan Vucci

AP Photo/Evan Vucci

SAUL LOEB/AFP via Getty Images

SAUL LOEB/AFP via Getty Images

Mark Hoffman/Milwaukee Journal-Sentinel via AP

Mark Hoffman/Milwaukee Journal-Sentinel via AP

House view: should the pollsters be fired?

The American opinion polls promised us a landslide victory in favour of Joe Biden.

Instead we were left with days on the edge of our seats. After a disaster in 2016, is it time to fire the pollsters?

Only if you consider a 90 per cent strike rate bad. It is better than I have done in many exams...

Popular vote versus the electoral college

Coming into election day, national polls gave Biden a decent 7 per cent lead. Investors were wrong to extrapolate a “Blue Wave” – where the Democrats take the presidency and Congress - from a large lead in the national polls.

The national poll itself is almost impossible to map on the electoral college, which is crucial, as we were reminded of in 2016.

Four years ago Donald Trump lost the popular vote but won the election. In other words, polls appear to better reflect the popular vote rather than the nuanced way the electoral college works.

Polls correct in most swing states

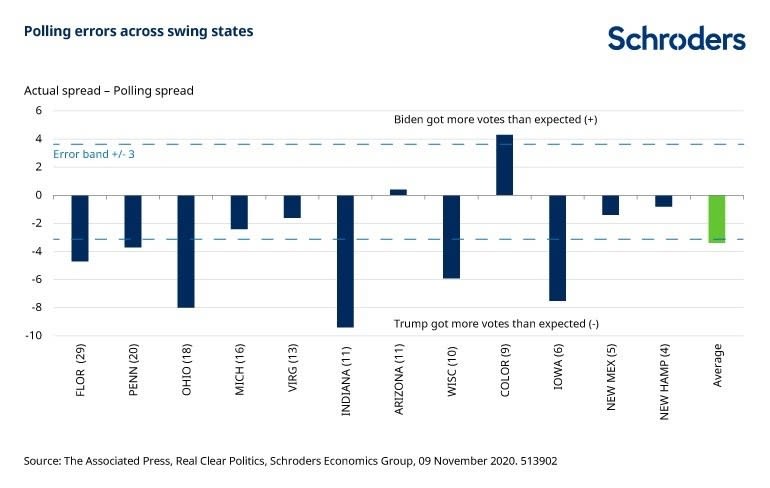

Polls in the swing states – which, stayed true to their “battleground” name - did pretty well.

Out of the 12 swing states we identified, 11 out of 12 had the correct prediction. Only Florida was wrong, pointing to a Biden lead. Even then, the predicted margin from pollsters of 1.4 per cent was well within the 3 per cent margin of error, so arguably should be excused.

Pollsters got the outcome of the swing states correct, but the vote margin was where they tripped up. For example, polls suggested Biden would win Florida by 1.4 per cent, but instead he lost by 3.3 per cent. So the margin of error for Florida – the most important swing state - was wrong by 4.7 per cent.

Various states also had large errors (see chart below), more than creeping outside the supposed 3%per cent margin of error. This error was not symmetric either; across the swing states, polls, on average polled Biden too favourably, by 3.4 per cent.

If we had the benefit of hindsight and were able to eliminate the bias by adding 3.4 per cent to Trump in each state, would polls have done better?

Polls would have correctly predicted Florida but, in an effort to do so, would have incorrectly predicted Arizona.

But with Florida worth more electoral college votes, this change would have better captured 3 per cent of the electoral college vote.

Michigan and Wisconsin – worth another 5 per cent of the vote - would have then also flagged up as narrow races. But most importantly, the polls would still have pointed to a convincing Biden victory.

Stepping back, it seems that investors were caught off guard by the large margin of error in Florida, which was widely seen as Biden’s ticket to a quick victory on the day of the election. Instead it was the combination of the sheer number of mail votes and the order by which states and mail votes were counted, that created the real uncertainty.

Pollsters should not be fired yet

With the correct outcome for the President and a 90 per cent hit rate in the swing states it would be unfair dismissal to fire the pollsters. But they do need to do some more work on eliminating bias, which is beginning to look more systemic than at first glance. We will put them on performance review and check-in in another four years.

Piya Sachdeva is an economist at Schroders

Bank your CPD here